|

Help

me add to this section. Submit your ideas or articles to bcolley@snet.net

Other Famous Links:

Joel Barlow, Anna

Huntington, Mark Twain

, Edward

Steichen

Charles

Ives: Musical Visionary

Cathy Laning, Katie Tkach

In

August of 1912, Charles Ives and his wife Harmony came to

West Redding and bought land on Umpawaug Hill, across the

road from the site of General Putnam's headquarters in the

Revolutionary War (corner of Umpawaug and Topstone Rd). They

had the house and barn built, and moved in a year later. This

was their country home for the rest of their lives. They would

come out from New York City in the early spring, and stay

until late in the fall. Ives commuted each morning by train

to his insurance office in the city, and he did much of his

music writing on this train.

For

many years they had a horse named "Rocket" who was

very much a member of the family. Ives would ride "Rocket"

down the hill to Sanford General Store near the train station.

They also had a Model T Ford. Umpawaug Road in those days

was just a dirt country road, filled with "thank you

ma'am's, as Ives's nephew Bigelow describes it. It wasn't

paved until 1928, and when it was, Ives got quite upset. He

was also outraged when the first airplanes began flying over,

and whenever he heard one he would come out and shake his

fist at it and shout "Get off my property!" He didn't

want anything to disrupt the peaceful country world of Umpawaug

Hill which he loved so much.

In

our quest to capture the essence of Charles Ives- revered

classical composer, interpreter of the American scene, and

the man- we talked with John Kirkpatrick, Paul Winter and

Luemily Ryder. The synthesis of their recollections provides

a composite sketch of this muscian.

John

Kirkpatrick is the curator of the Ives Collection at Yale.

He is a well known Ives authority and has come to know Ives's

music well.

In

1937 Kirkpatrick met Charles Ives. He had been corresponding

with him for ten years, but had never met him.

"I

can see him right there. I knew him during the last 17 years

of his life, and I saw him a few times each year. In a way

he was the most paradoxical man I've ever known. As a musician

he was both traditional and experimental. You could describe

his music best by saying there's no simple way to describe

it. That's part of the paradoxical nature he had.

"When

Ives first began to compose, his music was comparatively simple.

Many of his early pieces were influenced greatly by the church,

since he played the organ in church during his grammar school

years. At fourteen he was a salaried organist, the youngest

professional organist in the state.

"His

father was a musical "jack-of-all-trades". He was

even more versatile than his son.

"Ives

received his earliest muscial training from his father and

later from Horatio Parker at Yale. He attended Yale from 1894-1898.

From this time through his twenties he used both styles, experimental

and traditional, but he hardly ever showed his experiments

to Parker. At that period the simpler traditional style was

more acceptable than the complicated, experimental style.

Ives's music was different from itself all the time. It could

be very simple, or it could be very, very complex. There were

pieces that could be read and played with no effort, they

were the simple. And there were pieces that were so complicated

they are challenging, even today.

"You

know how you can look at a page of music and feel instinctively

if there is somthing real there or not? Well, there's something

real to Ives's music. There's always a core of something very

direct. and no matter how complicated it is, it hangs together

and communicates."

When

Charles Ives reached the peak of his experimental period,

he did not receive the recognition he deserved. The public

did not like being put to the inconvenience of having to try

hard to understand and play his music. "He knew exactly

how good a composer he was, and he knew exactly how far ahead

of his own time he was. It didn't bother him. Someone once

asked him why he didn't write music that people would like,

and he said 'I can't hear something else.' He anticipated

all the tricks of modern music in the first part of the 20th

century. Even though he was so far ahead of his time he still

deeply admired some of the classical composers- Bach, Beethoven,

and Brahms. He also admired the popular composers of the Civil

War Period. Although he enjoyed their styles, he had ideas

and opinions of his own.

"It

would be impossible to describe his music because it was so

paradoxical. You could never put your finger on it. You could

rarely get a definite answer to a question our of him. He

usually used your question as a springboard to other thoughts.

He was a genius. He was used to improvising and filling in;

he was much more of a musician than anybody realized.

"Charles

Ives knew that the kind of music he wanted to compose would

have no relation to his own times. Ives knew he would never

be able to support a family on it, so he deliberately financed

his composing through his insurance business. Many people

regard him as an insurance man doing music on the side. However,

he was a composer first and foremost, financing his non-conformist

composing through insurance, and showing the same genius in

both. There was a constant pressure living two lives a once.

Most people who come home from business want to relax. If

a composer finishes a symphony he naturally wants to relax

and perhaps celebrate. When Ives finished a symphony, most

likely late at night, he probably had time for only a little

sleep, before going downtown the next day for business. When

he got home from a day's business he would roll up his shirt

sleeves and start right into composing where he had left off

the previous night.

"Charles

Ives literally lived a double life. He was an insurance man

by day and a composer by night, on weekends, and during vacations.

Many of his business associates had no idea that he was even

interested in music. His musical friends never saw any trace

of his business life. He kept to himself a great deal, partly

because he treasured the time he wasn't actually engaged in

business, so he could compose. But he was both gregarious

and shy; like his music, Ives himself was a paradox."

At

Home with the Iveses

Luemily Ryder became a close friend of Charles Ives during

his years in Redding. She and her husband, Bill, lived next

door to Ives on Umpawaug Hill.

"Well

he was, shall I say, gentle, first; he was also a rebel and

he could be quite explosive. I think he was a religious person

and I think he was very understanding and considerate of the

downtrodden and the outcast. He was a great person.

"The

Iveses were people who often showed their kindness and generosity.

They were always doing something for other people. One family's

house was burned down and they offered their cottage. Here

the family stayed until a new house could be built.

"The

Iveses often lent their cottage out to poor people from the

city. It was similar to the Fresh-Air Organization (Branchville,

CT) that brings city children into the country for a vacation.

One summer the Iveses lent their cottage to the Osborne family.

the youngest Osborne child, Edith, was very ill. Mrs. Ives

graciously offered to take care of her. Edith gradually improved

in health under Mrs. Ives's care. The Ives grew immensely

fond of her and near the end of Edith's stay they approached

the Osbornes about adopting Edith. After much thought the

Osbornes consented.

"Children

loved Charles Ives. He would come out with his cane and shake

it in their facesm or he'd grab a child around the neck with

it and pull him toward him. The children would either be so

scared or so tickled that they'd giggle all over.

"Mrs.

Ives was just as loving as her husband. When she came down

to visit you could hear he whistling all the way down the

driveway.

"We

visited them in NYC many times and after dinner at their house

we would go into the living room. Mr. Ives would stretch out

on the couch. The room was dimly lit to rest his eyes so Mrs.

Ives would sit directly under the light to read the classics.

He liked that so much, just to listen to her read. That's

one of the nicest things I remember about them."

Mrs.

Ryder, herself a pianist and organist, went on to say, "His

music is beautiful. I really love it, even though it would

clash. I know he had all these sounds in his head that he

kept hearing and he would just bring them all together in

a composition. At first people did not accept it. There were

only a few that would play it. Most said it couldn't be played

because it was so difficult. That would make him mad because

he was so sure it could be played...

If

you are in Connecticut, I suggest a trip to New Haven to view

the Ives Collection at Yale University.

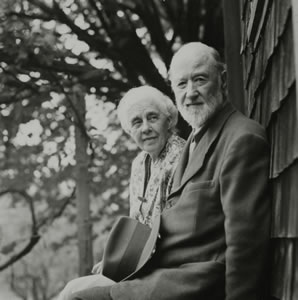

Ives outside his

West Redding home in 1946

Short

Bio:

Charles

Ives (1874 - 1954) was an American composer of classical music.

He is regarded as possibly the first American classical composer

of international significance. Ives was born on October 20,

1874 in Danbury, Connecticut, the son of a US Army bandmaster.

He was given music lessons by his father at an early age,

and later studied under Horatio Parker at Yale University.

After graduating, however, he decided to pursue a non-musical

career, believing that he would be forced to compromise his

musical ideals if he made a living from music. He therefore

followed a career in life insurance- While on vacation for

health concerns in 1906, Ives and his friend and colleague

Julius Myrick decided to form their own agency, Ives & Co.

(later to become Ives & Myrick). In a few years they had a

volume of business in insurance training that led the country

and would make Ives a very wealthy man. He composed music

in his spare time. Ives composed a number of works inspired

by nature and transcendentalism, including the Concord piano

sonata (c. 1916-1919) and the First Orchestral Set: Three

Places in New England (c. 1912-1921). Charles Ives was buried

in Wooster Cemetery in Danbury, Ct.

Coming

to Redding:

In

1912, Ives and his wife bought part of a farm in West Redding,

Connecticut, dividing their time between the farm and

New York City. The next few years produced such works as the

Fourth Symphony (c. 1912-1925) and the World War I-inspired

songs In Flanders Fields, He is there!, and Tom Sails Away

(all 1917).

Following

a serious heart attack in 1918, his health and productivity

declined; his last new pieces date from the mid-1920s. He

lived his last decades as an invalid in New York City and

West Redding, Conn., promoting his music as best he

could and revising pieces; meanwhile, various enthusiasts

gradually spread his music into the world.

Ives

Centennial Celebration Concert:

Some

2,000 people attended Redding's Ives Centennial Committee's

Aug. 18 1974 musical town meeting in a natural amphitheater

on property once owned by composer Charles Ives and heard

Paul Winter and his Consort. Jim Sinclair and Ken Singleton

were also involved in the Ives centennial celebration concert.

Organizing

the Barn:

Ives's

project, commencing in October 1934, to put his music in some

order in a huge built-in cabinet, newly constructed for him

in a former horse stall in the barn of his country house at

West Redding, Connecticut. But Ives's "system" for

Quality Photoprint Studio deteriorated into a state of chronic

confusion, probably because no one there could read music.

Ray Green, the new executive secretary of the American Music

Center, reported to Harmony Ives on 25 May 1950 that "the

master sheets [photostats] of Mr. Ives' works are in an extremely

chaotic condition. As a matter of fact, a careful and thorough

job of indexing needs to be done by a competent, reliable

and trained musician and researcher." Immediately following

Ives's death, John Kirkpatrick and the composer Henry Cowell

began jointly to bring all the manuscripts into one place

(drawing on their own holdings and on Ives's in his New York

apartment and the West Redding music room and its barn).

Alas,

Ives's filing system, even with supplementary file cabinets,

had become woefully jumbled. In his catalogue, Kirkpatrick

describes the disorder he found in June 1954: "Evidently he

was used to rummaging for things, pulling out whole fistfuls

from underneath which then became the top layer, so that each

drawer had been shuffled many times." Some identifications

of manuscripts were made quickly by the two men, but a huge

task lay ahead. A struggle for control of the collection ensued.

It was destined for the Library of Congress before Kirkpatrick

stepped in and convinced Mrs. Ives in January 1955 that Yale

University was the more appropriate repository (partly because

it was near Kirkpatrick's summer home in Georgetown, Connecticut,

and because Yale agreed to devote a separate "Ives Room" to

the storage of the manuscripts). However, the mass of nearly

seven thousand pages was moved temporarily to Edith Ives's

apartment in New York. There, Dr. Joseph Braunstein of the

New York Public Library staff began sorting and listing. Evidence

of his rudimentary system can be found written at the top

of a few manuscript pages. Sidney Cowell, Henry Cowell's wife,

presided over a general photostating of those pages that she

believed were not covered by the Quality photostat holdings

(which resulted in significant duplications). At Yale, over

the following years, the extant photostat negatives were stamped

on the back with a sequential numbering, and the photostating

continued as Kirkpatrick identified pages that had been missed.

In

the summer of 1955, Kirkpatrick took control of the project

from the Cowells and Braunstein. As he politely puts it in

his catalogue (p. v), "I gratefully took advantage of all

that Dr. Braunstein had done, and gradually coordinated everything

into a First List." An inveterate organizer with a pathological

love for jigsaw puzzles, Kirkpatrick trusted no one else's

work but his own. He started over with his own notes, rejoined

portions of manuscripts that had been torn apart, and began

building the most extraordinary catalogue that has ever honored

an American composer's work.

Nearly

all of Ives's manuscripts are safely collected in one place,

the Charles Ives Papers (MSS 14) in the Music Library of the

Yale University School of Music, New Haven, Connecticut. (For

years after their arrival at Yale University in September

1955, these manuscripts were known as the "Ives Collection.")

| |

|

|

| |

Charles

Ives and His World

by J. Peter Burkholder (Editor)

|

|

Back to TOP

| Back to Redding Section | Back

to Georgetown Section

|