|

Help

me add to this section. Submit your ideas or articles to bcolley@snet.net

For the latest

updates on our Twain 2010 projects, follow

me on Twitter.

View

a PowerPoint Presentation of Twain's

Time in Redding

Mark

Twain

Perhaps

the most famous person to have lived in Redding, only lived

in Redding for a year and six months. Regardless of the amount

of time he spent here, Redding, Connecticut loves

Mark Twain and reading through his life and works, there really

is no reason not to.

Mark

Twain in Redding CT Timeline

-

June 18, 1908:

Arrives in Redding

-

August, 1908:

Twain’s nephew drowns in NJ, he travels to NYC for funeral

& retires from NYC for good.

-

September 18,

1908: Burglars break

in to house.

The Burglary at Stormfield, September 18th, 1908.

This is quite an interesting story which is followed by

the burglar's own account.

-

October 1908:

Twain requires every male guest to leave $1 for library.

-

April 1909:

Daughter Jean arrives in Redding. (Lyon & Ashcroft

exit)

-

May 1909: Close

friend Henry Rogers dies.

-

June 1909:

Experiences heart pain & remains in bed most of June &

July.

-

August 1909:

Paine moves into Stormfield to aid Twain.

-

September

1909: 500 guests attend benefit for library fund.

-

October 6,

1909: Clara’s wedding celebrated at Stormfield.

-

November 19,

1909: Leaves for a month in “Bermooda”. Doctor’s orders.

-

December 20,

1909: Twain returns to Redding.

-

December 24,

1909: Daughter Jean dies while taking a bath. 40 acre

parcel of land Jean had called the Italian Farm sold to

build a Jean Clemens Wing on the Mark Twain Library.

-

January 1910:

He returns to Bermuda.

-

April 14, 1910:

Twain returns to Redding in very poor shape.

- April 21, 1910:

Twain woke suddenly, took Clara’s hand and said: “Goodbye

dear, if we meet....”.

Video

of Twain in Redding shot by Thomas Edison (1909)

The

following information is from Albert Bigelow Paine's Biography

of Mark Twain and Mark Twain's Speeches (New York: Harper

and Brothers, 1910) describes his times in Redding, Connecticut

(CT).

In

addition to the Paine information there are two more pages

of Twain in Redding, CT.

Also

available: New York Times Articles about Mark

Twain in Redding, CT. Very interesting and informative!

This page includes dates and articles on just about everything

that went on at Twain's Redding Connecticut home.

Quick

Links:

The

purchase of Stormfield

About Stormfield

Library Speech

His final return to Stormfield

From

"What Is Man?" and the Autobiography Chapter

248 of Albert Bigelow Paine, Mark Twain: A Biography (New

York: Harper & Brothers, 1912), 1321-1323.

Colonel

Harvey came to Dublin, NH that summer and persuaded Clemens

to let him print some selections from the dictations in the

new volume of the North American Review, which he proposed

to issue fortnightly. The matter was discussed a good deal,

and it was believed that one hundred thousand words could

be selected which would be usable forthwith, as well as in

that long-deferred period for which it was planned. Colonel

Harvey agreed to take a copy of the dictated matter and make

the selections himself, and this plan was carried out. It

may be said that most of the chapters were delightful enough;

though, had it been possible to edit them with the more positive

documents as a guide, certain complications might have been

avoided. It does not matter now, and it was not a matter of

very wide import then.

The

payment of these chapters netted Clemens thirty thousand dollars

-- a comfortable sum, which he promptly proposed to spend

in building on the property at Redding. He engaged John Mead

Howells to prepare some preliminary plans.

From

"The Boys' Life of Mark Twain", page 65 by

Albert Bigelow Paine.

The

house had been under construction for a year. He had never

seen it– never even seen the land I had bought for him. He

even preferred not to look at any plans or ideas for decoration.

“When

the house is finished and furnished, and the cat is purring

on the hearth, it will be time enough for me to see it,” he

had said more than once.

He

had only specified that the rooms should be large and that

the billiard-room should be red. His billiard-rooms thus far

had been of that color, and their memory was associated in

his mind with enjoyment and comfort. He detested details of

preparation, and then, too, he looked forward to the dramatic

surprise of walking into a home that had been conjured into

existence as with a word.

It

was the 18th of June, 1908, that he finally took possession.

The Fifth Avenue house was not dismantled, for it was the

plan then to use Stormfield only as a summer place. The servants,

however, with one exception, had been transferred to Redding,

and Mark Twain and I remained alone, though not lonely, in

the city house; playing billiards most of the time, and being

as hilarious as we pleased, for there was nobody to disturb.

I think he hardly mentioned the new home during that time.

He

had never seen even a photograph of the place, and I confess

I had moments of anxiety, for I had selected the site and

had been more or less concerned otherwise, though John Howells

was wholly responsible for the building. I did not really

worry, for I knew how beautiful and peaceful it all was.

The

morning of the 18th was bright and sunny and cool. Mark Twain

was up and shaved by six o’clock in order to be in time. The

train did not leave until four in the afternoon, but our last

billiards in town must begin early and suffer no interruption.

We were still playing when, about three, word was brought

up that the cab was waiting.

Arrived

at the station, a group collected, reporters and others, to

speed him to his new home. Some of the reporters came along.

The scenery was at its best that day, and he spoke of it approvingly.

The hour and a half required to cover the sixty miles’ distance

seemed short. The train porters came to carry out the bags.

He drew from his pocket a great handful of silver.

“Give

them something,” he said; “give everybody liberally that does

any service.”

There

was a sort of open-air reception in waiting–a varied assemblage

of vehicles festooned with flowers had gathered to offer gallant

country welcome. It was a perfect June evening, still and

dream-like; there seemed a spell of silence on everything.

The

people did not cheer–they smiled and waved to the white figure,

and he smiled and waved reply, but there was no noise. It

was like a scene in a cinema.

His

carriage led the way on the three-mile drive to the house

on the hilltop, and the floral procession fell in behind.

Hillsides were green, fields were white with daisies, dogwood

and laurel shone among the trees. He was very quiet as we

drove along. Once, with gentle humor, looking out over a white

daisy-field, he said:

“That

is buckwheat. I always recognize buckwheat when I see it.

I wish I knew as much about other things as I know about buckwheat.”

The

clear-running brooks, a swift-flowing river, a tumbling cascade

where we climbed a hill, all came in for his approval–then

we were at the lane that led to his new home, and the procession

behind dropped away.

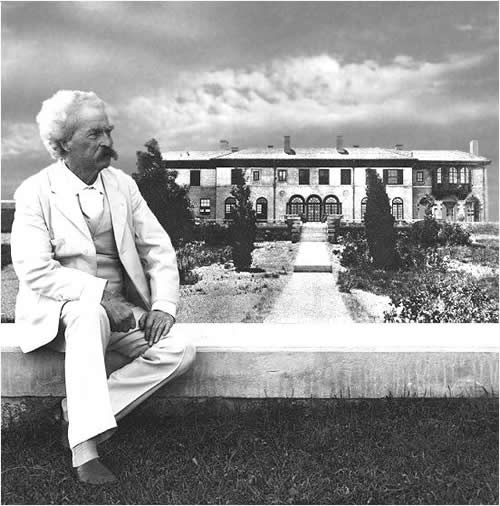

The

carriage ascended still higher, and a view opened across the

Saugatuck Valley, with its nestling village and church-spire

and farmhouses, and beyond them the distant hills. Then

came the house–simple in design, but beautiful–an Italian

villa, such as he had known in Florence, adapted here to American

climate and needs.

At

the entrance his domestic staff waited to greet him, and presently

he stepped across the threshold and stood in his own home

for the first time in seventeen years. Nothing was lacking–it

was as finished, as completely furnished, as if he had occupied

it a lifetime. No one spoke immediately, but when his eyes

had taken in the harmony of the place, with its restful, home-like

comfort, and followed through the open French windows to the

distant vista of treetops and farmsides and blue hills, he

said, very gently:

“How

beautiful it all is! I did not think it could be as beautiful

as this.” And later, when he had seen all of the apartments:

“It is a perfect house–perfect, so far as I can see, in every

detail. It might have been here always.”

There

were guests that first evening–a small home dinner-party–and

a little later at the foot of the garden some fireworks were

set off by neighbors inspired by Dan Beard, who had recently

located in Redding. Mark Twain, watching the rockets that

announced his arrival, said, gently:

“I

wonder why they go to so much trouble for me. I never go to

any trouble for anybody.”

The

evening closed with billiards, hilarious games, and when at

midnight the cues were set in the rack no one could say that

Mark Twain’s first day in his new home had not been a happy

one.

From

"Mark Twain: A Biographical Summary",

page 2 By Albert Bigelow Paine From Albert Bigelow Paine,

ed., Mark Twain's Letters (New York: Harper & Brothers,

1917).

His

life at Stormfield -- he had never seen the place until

the day of his arrival, June 18, 1908 -- was a peaceful and

serene old age. Not that he was really old; he never was that.

His step, his manner, his point of view, were all and always

young. He was fond of children and frequently had them about

him. He delighted in games -- especially in billiards -- and

in building the house at Stormfield the billiard-room was

first considered. He had a genuine passion for the sport;

without it his afternoon was not complete.

His

mornings he was likely to pass in bed, smoking -- he was always

smoking -- and attending to his correspondence and reading.

History and the sciences interested him, and his bed was strewn

with biographies and stories of astronomical and geological

research. The vastness of distances and periods always impressed

him. He had no head for figures, but he would labor for hours

over scientific calculations, trying to compass them and to

grasp their gigantic import. I remember once finding him highly

elated over the fact that he had figured out for himself the

length in hours and minutes of a "light year." He

showed me the pages covered with figures, and was more proud

of them than if they had been the pages of an immortal story.

Then we played billiards, but even his favorite game could

not make him altogether forget his splendid achievement.

From

"The Boys' Life of Mark Twain", page 65 by

Albert Bigelow Paine.

Mark

Twain loved Stormfield. Almost immediately he gave up the

idea of going back to New York for the winter, and I think

he never entered the Fifth Avenue house again. The quiet and

undisturbed comfort of Stormfield came to him at the right

time of life. His day of being the "Belle of New York” was

over. Now and then he attended some great dinner, but always

under protest. Finally he refused to go at all. He had much

company during that first summer–old friends, and now and

again young people, of whom he was always fond. The billiard-room

he called "the aquarium,” and a frieze of Bermuda fishes,

in gay prints, ran around the walls. Each young lady visitor

was allowed to select one of these as her patron fish and

attach her name to it. Thus, as a member of the "aquarium

club,” she was represented in absence. Of course there were

several cats at Stormfield, and these really owned the premises.

The kittens scampered about the billiard-table after the balls,

even when the game was in progress, giving all sorts of new

angles to the shots. This delighted him, and he would not

for anything have discommoded or removed one of those furry

hazards.

From

"Mark Twain: A Biographical Summary",

page 2 By Albert Bigelow Paine From Albert Bigelow Paine,

ed., Mark Twain's Letters (New York: Harper & Brothers,

1917).

It

was on the day before Christmas, 1909, that heavy bereavement

once more came into the life of Mark Twain. His daughter Jean,

long subject to epileptic attacks, was seized with a convulsion

while in her bath and died before assistance reached her.

He was dazed by the suddenness of the blow. His philosophy

sustained him. He was glad, deeply glad for the beautiful

girl that had been released. "I never greatly envied

anybody but the dead," he said, when he had looked at

her. "I always envy the dead." The coveted estate

of silence, time's only absolute gift, it was the one benefaction

he had ever considered worth while.

Yet

the years were not unkindly to Mark Twain. They brought him

sorrow, but they brought him likewise the capacity and opportunity

for large enjoyment, and at the last they laid upon him a

kind of benediction. Naturally impatient, he grew always more

gentle, more generous, more tractable and considerate as the

seasons passed. His final days may be said to have been spent

in the tranquil light of a summer afternoon. His own end followed

by a few months that of his daughter. There were already indications

that his heart was seriously affected, and soon after Jean's

death he sought the warm climate of Bermuda. But his malady

made rapid progress, and in April he returned to Stormfield.

He died there just a week later, April 21, 1910.

From

"Books and Burglars" By Mark Twain.

Address to The Redding (Conn.) Library Association, October

28, 1908. From Mark Twain's Speeches (New York: Harper and

Brothers, 1910).

Suppose

this library had been in operation a few weeks ago, and

the burglars who happened along and broke into my house --

taking a lot of things they didn't need, and for that matter

which I didn't need -- had first made entry into this institution.

Picture them seated here on the floor, poring by the light

of their dark-lanterns over some of the books they found,

and thus absorbing moral truths and getting a moral uplift.

The whole course of their lives would have been changed. As

it was, they kept straight on in their immoral way and were

sent to jail. For all we know, they may next be sent to Congress.

And, speaking of burglars, let us not speak of them too harshly.

Now, I have known so many burglars -- not exactly known, but

so many of them have come near me in my various dwelling-places,

that I am disposed to allow them credit for whatever good

qualities they possess. Chief among these, and, indeed, the

only one I just now think of, is their great care while doing

business to avoid disturbing people's sleep. Noiseless as

they may be while at work, however, the effect of their visitation

is to murder sleep later on. Now we are prepared for these

visitors. All sorts of alarm devices have been put in the

house, and the ground for half a mile around it has been electrified.

The burglar who steps within this danger zone will set loose

a bedlam of sounds, and spring into readiness for action our

elaborate system of defences. As for the fate of the trespasser,

do not seek to know that. He will never be heard of more.

From

"The Voyage Home" Chapter 292 of

Albert Bigelow Paine, Mark Twain: A Biography (New York: Harper

& Brothers, 1912), 1564-1574.

I

sent no word to Bermuda that I was coming, and when on

the second morning I arrived at Hamilton, I stepped quickly

ashore from the tender and hurried to Bay House. The doors

were all open, as they usually are in that summer island,

and no one was visible. I was familiar with the place, and,

without knocking, I went through to the room occupied by Mark

Twain. As I entered I saw that he was alone, sitting in a

large chair, clad in the familiar dressing-gown.

Bay

House stands upon the water, and the morning light, reflected

in at the window, had an unusual quality. He was not yet shaven,

and he seemed unnaturally pale and gray; certainly he was

much thinner. I was too startled, for the moment, to say anything.

When he turned and saw me he seemed a little dazed. "Why,"

he said, holding out his hand, "you didn't tell us you

were coming." "No," I said, "it is rather

sudden. I didn't quite like the sound of your last letters."

"But those were not serious," he protested. "You

shouldn't have come on my account." I said then that

I had come on my own account; that I had felt the need of

recreation, and had decided to run down and come home with

him. "That's -- very -- good," he said, in his slow,

gentle fashion. "Now I'm glad to see you."

His

breakfast came in and he ate with an appetite. When he had

been shaved and freshly propped up in his pillows it seemed

to me, after all, that I must have been mistaken in thinking

him so changed. Certainly he was thinner, but his color was

fine, his eyes were bright; he had no appearance of a man

whose life was believed to be in danger. He told me then of

the fierce attacks he had gone through, how the pains had

torn at him, and how it had been necessary for him to have

hypodermic injections, which he amusingly termed "hypnotic

injunctions" and "subcutaneous applications,"

and he had his humor out of it, as of course he must have,

even though Death should stand there in person.

From

Mr. and Mrs. Allen and from the physician I learned how slender

had been his chances and how uncertain were the days ahead.

Mr. Allen had already engaged passage on the Oceana for the

12th, and the one purpose now was to get him physically in

condition for the trip. How devoted those kind friends had

been to him! They had devised every imaginable thing for his

comfort. Mr. Allen had rigged an electric bell which connected

with his own room, so that he could be aroused instantly at

any hour of the night. Clemens had refused to have a nurse,

for it was only during the period of his extreme suffering

that he needed any one, and he did not wish to have a nurse

always around. When the pains were gone he was as bright and

cheerful, and, seemingly, as well as ever.

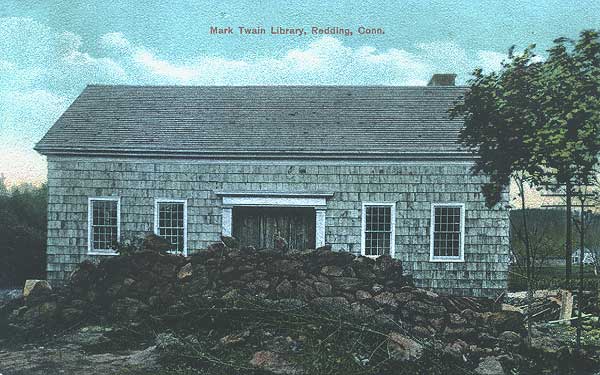

On

the afternoon of my arrival we drove out, as formerly, and

he discussed some of the old subjects in quite the old way.

He had been re-reading Macaulay, he said, and spoke at considerable

length of the hypocrisy and intrigue of the English court

under James II. He spoke, too, of the Redding

Library. I had sold for him that portion of

the land where Jean's farm-house had stood, and it was in

his mind to use the money for some sort of a memorial to Jean.

I had written, suggesting that perhaps he would like to put

up a small library building, as the Adams lot faced the corner

where Jean had passed every day when she rode to the station

for the mail. He had been thinking this over, he said, and

wished the idea carried out. He asked me to write at once

to his lawyer, Mr. Lark, and have a paper prepared appointing

trustees for a memorial library fund.

The

pain did not trouble him that afternoon, nor during several

succeeding days. He was gay and quite himself, and he often

went out on the lawn; but we did not drive out again. For

the most part, he sat propped up in his bed, reading or smoking,

or talking in the old way; and as I looked at him he seemed

so full of vigor and the joy of life that I could not convince

myself that he would not outlive us all.

I

found that he had been really very much alive during those

three months -- too much for his own good, sometimes -- for

he had not been careful of his hours or his diet, and had

suffered in consequence. He had not been writing, though he

had scribbled some playful valentines and he had amused himself

one day by preparing a chapter of advice -- for me it appeared

-- which, after reading it aloud to the Allens and receiving

their approval, he declared he intended to have printed for

my benefit. As it would seem to have been the last bit of

continued writing he ever did, and because it is characteristic

and amusing, a few paragraphs may be admitted.

The

"advice" is concerning deportment on reaching the

Gate which St. Peter is supposed to guard: Upon arrival do

not speak to St. Peter until spoken to. It is not your place

to begin. Do not begin any remark with "Say." When

applying for a ticket avoid trying to make conversation. If

you must talk let the weather alone. St. Peter cares not a

damn for the weather. And don't ask him what time the 4:30

train goes; there aren't any trains in heaven, except through

trains, and the less information you get about them the better

for you. You can ask him for his autograph -- there is no

harm in that -- but be careful and don't remark that it is

one of the penalties of greatness. He has heard that before.

Don't try to kodak him. Hell is full of people who have made

that mistake. Leave your dog outside. Heaven goes by favor.

If it went by merit you would stay out and the dog would go

in. You will be wanting to slip down at night and smuggle

water to those poor little chaps (the infant damned), but

don't you try it. You would be caught, and nobody in heaven

would respect you after that. Explain to Helen why I don't

come. If you can. There were several pages of this counsel.

One paragraph was written in shorthand. I meant to ask him

to translate it; but there were many other things to think

of, and I did not remember.

I

spent most of each day with him, merely sitting by the bed

and reading while he himself read or dozed. His nights were

wakeful -- he found it easier to sleep by day -- and he liked

to think that some one was there. He became interested in

Hardy's Jude, and spoke of it with high approval, urging me

to read it. He dwelt a good deal on the morals of it, or rather

on the lack of them. He followed the tale to the end, finishing

it the afternoon before we sailed. It was his last continuous

reading. I noticed, when he slept, that his breathing was

difficult, and I could see from day to day that he did not

improve; but each evening he would be gay and lively, and

he liked the entire family to gather around, while he became

really hilarious over the various happenings of the day.

It

was only a few days before we sailed that the very severe

attacks returned. The night of the 8th was a hard one. The

doctors were summoned, and it was only after repeated injections

of morphine that the pain had been eased. When I returned

in the early morning he was sitting in his chair trying to

sing, after his old morning habit. He took my hand and said:

"Well, I had a picturesque night. Every pain I had was

on exhibition." He looked out the window at the sunlight

on the bay and green dotted islands. "'Sparkling and

bright in the liquid light,'" he quoted. "That's

Hoffman. Anything left of Hoffman?" "No," I

said. "I must watch for the Bermudian and see if she

salutes," he said, presently. "The captain knows

I am here sick and he blows two short whistles just as they

come up behind that little island. Those are for me."

He said he could breathe easier if he could lean forward,

and I placed a card-table in front of him.

His

breakfast came in, and a little later he became quite gay.

He drifted to Macaulay again, and spoke of King James's plot

to assassinate William II., and how the clergy had brought

themselves to see that there was no difference between killing

a king in battle and by assassination. He had taken his seat

by the window to watch for the Bermudian. She came down the

bay presently, her bright-red stacks towering vividly above

the green island. It was a brilliant morning, the sky and

the water a marvelous blue. He watched her anxiously and without

speaking. Suddenly there were two white puffs of steam, and

two short, hoarse notes went up from her. "Those are

for me," he said, his face full of contentment. "Captain

Fraser does not forget me."

There

followed another bad night. My room was only a little distance

away, and Claude came for me. I do not think any of us thought

he would survive it; but he slept at last, or at least dozed.

In the morning he said: "That breast pain stands watch

all night and the short breath all day. I am losing enough

sleep to supply a worn-out army. I want a jugful of that hypnotic

injunction every night and every morning." We began to

fear now that he would not be able to sail on the 12th; but

by great good-fortune he had wonderfully improved by the 11th,

so much so that I began to believe, if once he could be in

Stormfield, where the air was more vigorous, he might easily

survive the summer. The humid atmosphere of the season increased

the difficulty of his breathing.

That

evening he was unusually merry. Mr. and Mrs. Allen and Helen

and myself went in to wish him good night. He was loath to

let us leave, but was reminded that he would sail in the morning,

and that the doctor had insisted that he must be quiet and

lie still in bed and rest. He was never one to be very obedient.

A little later Mrs. Allen and I, in the sitting-room, heard

some one walking softly outside on the veranda. We went out

there, and he was marching up and down in his dressing-gown

as unconcerned as if he were not an invalid at all. He hadn't

felt sleepy, he said, and thought a little exercise would

do him good. Perhaps it did, for he slept soundly that night

-- a great blessing.

Mr.

Allen had chartered a special tug to come to Bay House landing

in the morning and take him to the ship. He was carried in

a little hand-chair to the tug, and all the way out he seemed

light-spirited, anything but an invalid. The sailors carried

him again in the chair to his state-room, and he bade those

dear Bermuda friends good-by, and we sailed away. As long

as I remember anything I shall remember the forty-eight hours

of that homeward voyage. It was a brief two days as time is

measured; but as time is lived it has taken its place among

those unmeasured periods by the side of which even years do

not count.

At

first he seemed quite his natural self, and asked for a catalogue

of the ship's library, and selected some memoirs of the Countess

of Cardigan for his reading. He asked also for the second

volume of Carlyle's French Revolution, which he had with him.

But we ran immediately into the more humid, more oppressive

air of the Gulf Stream, and his breathing became at first

difficult, then next to impossible. There were two large port-holes

which I opened; but presently he suggested that it would be

better outside. It was only a step to the main-deck, and no

passengers were there. I had a steamer-chair brought, and

with Claude supported him to it and bundled him with rugs;

but it had grown damp and chilly, and his breathing did not

improve. It seemed to me that the end might come at any moment,

and this thought was in his mind, too, for once in the effort

for breath he managed to say: "I am going -- I shall

be gone in a moment." Breath came; but I realized then

that even his cabin was better than this. I steadied him back

to his berth and shut out most of that deadly dampness. He

asked for the "hypnotic injunction" (for his humor

never left him), and though it was not yet the hour prescribed

I could not deny it. It was impossible for him to lie down,

even to recline, without great distress. The opiate made him

drowsy, and he longed for the relief of sleep; but when it

seemed about to possess him the struggle for air would bring

him upright.

During

the more comfortable moments he spoke quite in the old way,

and time and again made an effort to read, and reached for

his pipe or a cigar which lay in the little berth hammock

at his side. I held the match, and he would take a puff or

two with satisfaction. Then the peace of it would bring drowsiness,

and while I supported him there would come a few moments,

perhaps, of precious sleep. Only a few moments, for the devil

of suffocation was always lying in wait to bring him back

for fresh tortures. Over and over again this was repeated,

varied by him being steadied on his feet or sitting on the

couch opposite the berth.

In

spite of his suffering, two dominant characteristics remained

-- the sense of humor, and tender consideration for another.

Once when the ship rolled and his hat fell from the hook,

and made the circuit of the cabin floor, he said: "The

ship is passing the hat." Again he said: "I am sorry

for you, Paine, but I can't help it -- I can't hurry this

dying business. Can't you give me enough of the hypnotic injunction

to put an end to me?" He thought if I could arrange the

pillows so he could sit straight up it would not be necessary

to support him, and then I could sit on the couch and read

while he tried to doze. He wanted me to read Jude, he said,

so we could talk about it. I got all the pillows I could and

built them up around him, and sat down with the book, and

this seemed to give him contentment. He would doze off a little

and then come up with a start, his piercing, agate eyes searching

me out to see if I was still there. Over and over -- twenty

times in an hour -- this was repeated.

When

I could deny him no longer I administered the opiate, but

it never completely possessed him or gave him entire relief.

As I looked at him there, so reduced in his estate, I could

not but remember all the labor of his years, and all the splendid

honor which the world had paid to him. Something of this may

have entered his mind, too, for once, when I offered him some

of the milder remedies which we had brought, he said: "After

forty years of public effort I have become just a target for

medicines." The program of change from berth to the floor,

from floor to the couch, from the couch back to the berth

among the pillows, was repeated again and again, he always

thinking of the trouble he might be making, rarely uttering

any complaint; but once he said: "I never guessed that

I was not going to outlive John Bigelow." And again:

"This is such a mysterious disease. If we only had a

bill of particulars we'd have something to swear at."

Time and again he picked up Carlyle or the Cardigan Memoirs,

and read, or seemed to read, a few lines; but then the drowsiness

would come and the book would fall. Time and again he attempted

to smoke, or in his drowse simulated the motion of placing

a cigar to his lips and puffing in the old way.

Two

dreams beset him in his momentary slumber -- one of a play

in which the title-role of the general manager was always

unfilled. He spoke of this now and then when it had passed,

and it seemed to amuse him. The other was a discomfort: a

college assembly was attempting to confer upon him some degree

which he did not want. Once, half roused, he looked at me

searchingly and asked: "Isn't there something I can resign

and be out of all this? They keep trying to confer that degree

upon me and I don't want it." Then realizing, he said:

"I am like a bird in a cage: always expecting to get

out and always beaten back by the wires." And, somewhat

later: "Oh, it is such a mystery, and it takes so long."

Toward the evening of the first day, when it grew dark outside,

he asked: "How long have we been on this voyage?"

I answered that this was the end of the first day. "How

many more are there?" he asked. "Only one, and two

nights." "We'll never make it," he said. "It's

an eternity." "But we must on Clara's account,"

I told him, and I estimated that Clara would be more than

half-way across the ocean by now. "It is a losing race,"

he said; "no ship can outsail death." It has been

written -- I do not know with what proof -- that certain great

dissenters have recanted with the approach of death -- have

become weak, and afraid to ignore old traditions in the face

of the great mystery.

I

wish to write here that Mark Twain, as he neared the end,

showed never a single tremor of fear or even of reluctance.

I have dwelt upon these hours when suffering was upon him,

and death the imminent shadow, in order to show that at the

end he was as he had always been, neither more nor less, and

never less than brave. Once, during a moment when he was comfortable

and quite himself, he said, earnestly: "When I seem to

be dying I don't want to be stimulated back to life. I want

to be made comfortable to go." There was not a vestige

of hesitation; there was no grasping at straws, no suggestion

of dread.

Somehow

those two days and nights went by. Once, when he was partially

relieved by the opiate, I slept, while Claude watched, and

again, in the fading end of the last night, when we had passed

at length into the cold, bracing northern air, and breath

had come back to him, and with it sleep. Relatives, physicians,

and news-gatherers were at the dock to welcome him. He was

awake, and the northern air had brightened him, though it

was the chill, I suppose, that brought on the pains in his

breast, which, fortunately, he had escaped during the voyage.

It was not a prolonged attack, and it was, blessedly, the

last one. An invalid-carriage had been provided, and a compartment

secured on the afternoon express to Redding

-- the same train that had taken him there two years before.

Dr.

Robert H. Halsey and Dr. Edward Quintard attended him, and

he made the journey really in cheerful comfort, for he could

breathe now, and in the relief came back old interests. Half

reclining on the couch, he looked through the afternoon papers.

It happened curiously that Charles Harvey Genung, who, something

more than four years earlier, had been so largely responsible

for my association with Mark Twain, was on the same train,

in the same coach, bound for his country-place at New Hartford.

Lounsbury was waiting with the carriage, and on that still,

sweet April evening we drove him to Stormfield much as we

had driven him two years before.

Now

and then he mentioned the apparent backwardness of the season,

for only a few of the trees were beginning to show their green.

As we drove into the lane that led to the Stormfield entrance,

he said: "Can we see where you have built your billiard-room?"

The gable showed above the trees, and I pointed it out to

him. "It looks quite imposing," he said. I think

it was the last outside interest he ever showed in anything.

He had been carried from the ship and from the train, but

when we drew up to Stormfield, where Mrs. Paine, with Katie

Leary and others of the household, was waiting to greet him,

he stepped from the carriage alone with something of his old

lightness, and with all his old courtliness, and offered each

one his hand. Then, in the canvas chair which we had brought,

Claude and I carried him up-stairs to his room and delivered

him to the physicians, and to the comforts and blessed air

of home. This was Thursday evening, April 14, 1910.

History

of Redding Resources:

New

York Times Articles about Mark Twain in Redding

Photographs

of Stormfield with a very descriptive write up of the

house's rooms and layout.

The

Stormfield Project has begun, you can track it via my Mark

Twain Stormfield Project blog.

For

the latest updates on our Twain 2010 projects, follow

us on Twitter.

View

a PowerPoint Presentation of Twain's

Time in Redding

Twain

Quote T-Shirts

(fundraiser for Twain 2010 projects)

Additional

Resources:

www.twainquotes.com

Great Resource

www.twainweb.net

The Mark Twain Forum (amazing insights).

Here's

a scrapbook with pictures of Stormfield from PBS. Click Here.

Resource

with links to Twain related sites

Twain

Quote T-Shirts

Back to TOP

| Back to Redding Section | Back

to Georgetown Section

|

|