|

This

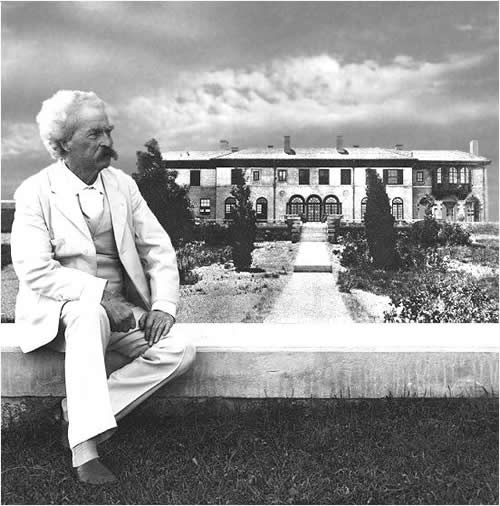

information on Mark Twain's final residence, Stormfield. Help

me add to this section. Submit your ideas or articles to bcolley@snet.net

View

a PowerPoint Presentation of Twain's

Time in Redding

Mark

Twain's Arrival in Redding, CT:

“On

the 18th of June, 1908, at about four in the afternoon we

left New York City by an express train that was to make its

first stop in Redding that day. With Mr. Clemens were my father,

a reporter or two, a photographer and that most fortunate

little girl, myself, whose boarding school closed that day

so that I, too, was homeward bound to Redding.

Waiting

for us at the Redding station was a proud array of carriages,

flower trimmed, and filled with smiling people who waved warmly.

I knew I would never forget it. Mr. Clemens waved in return,

then stepped into his own carriage and drove toward the beautiful

house that was to be his last home. “

-Louise

Paine

New

York Times: "Do you like it here at Stormfield?"

Samuel

Clemens: "Yes, it is the most out of the world and peaceful

and tranquil and in every way satisfactory home I have had

experience of in my life."

“I

was never in this beautiful region until yesterday evening.

Miss Lyon and the architect built and furnished the house

without any help or advice from me, and the result is entirely

to my satisfaction.

It is charmingly quiet here. The house stands alone, with

nothing in sight but woodsy hills and rolling country.”

-Samuel

L. Clemens letter to Dorothy Quick dated June 19, 1908

Mark

Twain in Redding CT Timeline

-

June 18, 1908:

Arrives in Redding

-

August, 1908:

Twain’s nephew drowns in NJ, he travels to NYC for funeral

& retires from NYC for good.

-

September 18,

1908: Burglars break

in to house.

The

Burglary at Stormfield, September 18th, 1908. This

is quite an interesting story which is followed by the

burglar's own account.

-

October 1908:

Twain requires every male guest to leave $1 for library.

-

December 1908:

Just before Christmas Samuel L. Clemens at his place here

got word from his friend Robert J. Collier of New York,

that the latter would send him an elephant as a present.

This caused much anxiety at the Clemens household, especially

Miss Lyon who contacted Mr. Collier to explain there was

simply no room for an elephant at Stormfield…Collier replied

“oh, just put him in the garage.”�The ‘elephant’ arrived

on Christmas morning. It turned out to be a toy elephant

about as large as a good sized calf and mounted on wheels.

-

April 1909:

Daughter Jean arrives in Redding.

-

May 1909: Close

friend Henry Rogers dies.

-

June 1909:

Experiences heart pain & remains in bed most of June &

July.

-

August 1909:

Paine moves into Stormfield to aid Twain.

-

September

1909: 500 guests attend benefit for library fund.

-

October 6,

1909: Clara’s wedding celebrated at Stormfield.

-

November 19,

1909: Leaves for a month in “Bermooda”. Doctor’s orders.

-

December 20,

1909: Twain returns to Redding.

-

December 24,

1909: Daughter Jean dies while taking a bath. 40 acre

parcel of land Jean had called the Italian Farm sold to

build a Jean Clemens Wing on the Mark Twain Library.

-

January 1910:

He returns to Bermuda.

-

April 14, 1910:

Twain returns to Redding in very poor shape.

- April 21, 1910:

Twain woke suddenly, took Clara’s hand and said: “Goodbye

dear, if we meet....”.

Video

of Twain in Redding shot by Thomas Edison (1909)

Post-Twain

Highlights of Stormfield and Related Properties

-

May 8, 1910:

The last will and testiment of Samuel L. Clemens filed

in Redding. The will was dated Aug. 17, 1909, and covers

eight typewritten pages. It was drawn in Redding and witnessed

by Mr. Clemens's secretary, Albert Bigelow Paine, Harry

Lounsbury, Superintendent of Mr. Clemens's estate, and

Charles G. Lark of New York.

-

July 10, 1910:

Mrs. Clara Clemens-Gabrilowitsch, daughter of the late

Samuel L. Clemens, (Mark Twain,) has formally notified

the directors of the Mark Twain Free Library here that

she will present to that institution practically the entire

library of her father, now in the Redding residence, Stormfield.

The gift includes nearly 2,500 volumes.

-

February 19,

1911: The Mark Twain Library, built as a memorial to Miss

Jean L. Clemens, daughter of the humorist, who was drowned

in a bathtub in her father's home, Stormfield, on Dec.

24, 1909, was formally dedicated this afternoon. Addresses

were made by the Rev. Joseph H. Twichell of Hartford and

the Rev. Frederick Winslow Adams of Schenectady, N. Y.

-

July 20, 1912:

The public library founded by the late Samuel L. Clemens

(Mark Twain) in Redding, Conn., where he spent the latter

years of his life, has been endowed by Andrew Carnegie

with a fund sufficient to support it. The library is to

be known as the Mark Twain Memorial Library.

-

July 2, 1917:

Humorist's Daughter Finds Connecticut Place Too Isolated.

Stormfield, Mark Twain's old home near Redding, Conn.,

has been advertised for sale. He built it with the idea

of getting a country home which should be near enough

to New York, and yet not too near, in Summer and Winter;

but his daughter, Mrs. Clara Clemens Gabrilowitsch, to

whom it passed after his death, found it too far away

for the needs of an artist whose affairs required frequent

presence in the metropolis.

-

October 25,

1918: Stormfield, the estate at Redding, Conn., which

was the home of Mark Twain, has been given by his daughter,

Clara Clemens (Mme. Ossip Gabrilowitsch) for the use of

convalescent soldiers and sailors of the artistic professions.

Mme. Gabrilowitsch, though admitting that she had turned

Stormfield over for the use of wounded men would not discuss

the subject further, saying that the affairs of the organization

which was to control the estate were not yet complete.

-

March 23, 1923

Mark Twain Estate Sold. The trustees of the Samuel L.

Clemens estate have sold "Stormfield," near Redding, Conn.,

to Mrs. Margaret E. Given. The property contains abut

200 acres, with a stucco residence of Italian architecture,

containing eighteen rooms and five baths built in 1907

and occupied by Mr. Clemens (Mark Twain, the world famous

humorist) until his death in 1910. Hamilton Iselin & Co.

were the brokers in the deal.

-

July 25, 1923:

Stormfield - the home of Samuel L. Clemens (Mark Twain),

in the closing years of his life - was burned early today.

The picturesque villa on the ridge of this town was unoccupied

for many years after Mr. Clemens's death, but was bought

in December by Mrs. Margaret E. Givens of New York, as

a Summer home.

-

April 18, 1924:

The Mark Twain property, where stand the ruins of the

former home of the author(house burned down), has been

sold to George Leland Hunter, who, it is understood, represents

a wealthy New York man who is expected to erect an elaborate

residence on the site. Mr. Hunter recently purchased and

occupies the house known as The Lobster Pot, given by

Mark Twain to his social secretary, Miss Virginia Lyon.

He is author of several books on tapestries.

- October 8, 1953:

A defective oil burner was blamed today for a $100,000 blaze

that destroyed a two-century-old house once owned by Mark

Twain known as the Lobster Pot. The estimate of the damage

was made by the present owner, the Rev. Anson Phelps Stokes

Jr., rector of St. Bartholomew's Protestant Episcopal Church,

New York, who acquired the twelve-room landmark in 1952

as a summer home. The blaze yesterday afternoon destroyed

many antiques, including family heirlooms, according to

the owner, who said the loss was partially covered by insurance.

Stormfield

Guestbook

Guestbook

entries are written by Samuel L. Clemens:

Guestbook's

Opening Pages- I bought this farm of 200 acres three years

ago, on the suggestion of Albert Bigelow Paine, who said its

situation and surroundings would content me- a prophecy which

came true 3 years later, when I arrived on the ground. John

Howells, architect and Clara Clemens and Miss Lyon planned

the house without help from me, and began to build it in June

1907. When I arrived a year later it was all finished and

furnished and swept and garnished and it was as homey and

cozy and comfortable as if it had been occupied a generation.

This was the 18th of June in the present year [1908] I only

came to spend the summer, but I shan't go away anymore.

We

installed a guest-book June 27th and used it until four days

ago, when this new and more satisfactory one arrived from

the hand of my niece Mary Rogers and put it out of commission.

I have transferred the names from that one to this one. The

autographing of signatures will now be resumed. Has been resumed,

I should say: that charming Billie Burke was the first guest

to arrive after the coming of the book, and she inaugurated

the resuming, her signature heads the page under the date

of December 27.

S.L.

Clemens

Dec. 29, 1908

"In

peace and honor rest you here, my guest; repose you here,

Secure from worldly chances and mishaps! Here lurks no treason,

here no envy swells, Here grows no damned grudges; here are

no storms, No noise, but silence and eternal sleep: In peace

and honor rest you here, my guest!"

Titus

Andronicus, Act I, Scene I

Helen

Keller's guestbook entry January 11, 1909:

"I

have been in Eden three days and I saw a King. I knew he was

a King the minute I touched him though I had never touched

a King before."

-A

daughter of Eve. Helen Keller

Jan. 11

The

guestbook at the Mark Twain Library is in fair shape and it

is a copy. It is noted as being given to the library in 1935.

The original is with UC Berkeley.

Description

of Stormfield from: MEMORIES OF MARK TWAIN IN BERMUDA

Many

minutes before we reached it we could see the peaceful white

Italian villa, from whose many windows we knew we could look

for miles over the country. The grounds were unspoiled by

the hand of the landscape gardener, and bushes grew everywhere,

while the graveled road, that led up to the entrance, was

not yet hardened by excessive travel. We drove up to the door.

It opened, and there stood Mr. Clemens. It might have been

yesterday that I had seen him last, for he had not changed.

His suit was as white and immaculate as ever, his hair as

silvery. There was only one change. He had tied a bow of pink

ribbon to the top locks of his head, in honor of the guest.

He extended both hands in cordial greeting, and I knew then

that the Happy Island had not been a dream. The bow of pink

ribbon was gently referred to, with proper acknowledgment

of its hospitable significance. Mr. Clemens received the thanks

gravely, and then the ornament placed there whimsically was

apparently forgotten, but remained coquettishly pert all the

rest of the evening.

Even

before I went to my room I must look over the house. So we

went from living room to loggia and back again to the dining

room, and then down to the pergola, back again to the house

and into the billiard-room, then upstairs to catch a glimpse

of the view from Mr. Clemens' room before the twilight should

close in upon it. Then Clara Clemens's charming suite of rooms

must be visited, then the other bed-rooms, and the guest rooms.

We must have a peep also into the servants' quarters, but

finally, we stopped, before reaching the attic, which was

reserved to another time.

The

house was designed by the son of his life-long friend, Mr.

W. D. Howells, a fact which gave Mr. Clemens great satisfaction.

It was singularly in keeping with the dark, straight cedars

which nature had foreseeingly disposed in decorative lines

and groups. In side there was spaciousness, light, perfect

comfort, and simplicity: while outside there was all the beauty

of a New England landscape at its best, with nothing abrupt

or harsh in the undulating curves of its hills and valleys;

with something maternal in its soft, full outlines -- where

it would seem a sweet and restful thing to lay one's tired

body down and let this mother Earth soothe and enfold you.

Mr.

Clemens told me, almost with glee, that he had never seen

either house or land until one day, the preceding June, when

he came and took possession of a fully furnished and settled

kingdom. All the instructions he had given were, that his

room should be a quiet one, that the billiard-room should

be big enough so that when he played he would not have to

jab his cue into the wall, and that there should be a living-room

at least forty by twenty feet. He was perfectly satisfied

with the result, and wandered delightedly from room to room

as he pointed out this and that particular charm.

As

twilight fell, we gathered about the big fireplace in the

living-room. Mr. Clemens asked me if I noticed anything very

peculiar about the room. I vainly tried to perceive some eccentricity,

but could not, for everything was in perfect harmony. "Haven't

you noticed," said he, "that there isn't a picture on the

walls?" I had to confess that I hadn't. We sat and talked

of our friends of the Happy Island -- of the Rajah, and of

Margaret and the other Angel-fish, until it was time to go

and dress for dinner.

This

was a function where conversation was as important as food.

Mr. Clemens grew restless before many courses had been served,

and rose, to walk up and down the dining-room, discoursing

the while on some favorite topic. This he often did at meals.

For he was not a hearty eater, except spasmodically, and so

he would often suddenly rise, still talking, and continue

his tirade while pacing the floor. Then, if another course

tempted him, he would come back and partake of it.

There

was a big organ at one end of the living-room, with a self-playing

attachment, and after dinner we had some music. One of the

guests played while we sat in the fire light, and Mr. Clemens

in his big armchair smoked and was perfectly happy.

Mr.

Clemens spent half of each morning in bed, and sometimes he

did not appear until lunch-time; but the morning after Thanksgiving

he was downstairs at ten, and proposed that we take a walk

over the hills, his hills. It was a gloriously bright, crisp,

cold day, and the atmosphere was so limpid that we could see

far away. Mr. Clemens put on a fur-lined great-coat and his

gray cap, saw that there was a goodly supply of cigars in

his pockets, and we started off down the walk, through the

pergola, and picked our way to a winding path that led us

to all sorts of charming places.

Just

as we were starting from the house, Mr. Clemens had stopped

me and had said: "I want you to look at this view." I looked

at the slope below, that dipped down into a pretty valley,

and then at the gentle hills beyond, where winter had forced

the trees to drop their sheltering screens, so that unexpected

houses and isolated farms were here and there revealed. Mr.

Clemens asked, "Do you see that white building over there?"

pointing, at the same time, to what was unmistakably a country

church. He went on: "We've just discovered that it is a church.

It's the nearest one. Just at a safe distance. All summer

we thought that it was a wind mill."

That

morning walk in the white November sunlight will always remain

a vivid memory. We scrambled down the hillside and came to

the stream, which Mr. Clemens pointed out to me with the proud

gesture of a discoverer. It was just what a New England stream

should be, winding and clear, flowing at times turbulently

over obstructing stones, and then pausing to form a still,

golden-brown pool. We followed its windings with happy delight,

finding new beauties to show to each other and to exclaim

over. Mr. Clemens told me Indian stories and legends he had

heard in his boyhood days.

We

came to a tiny cave, at the side of the road, where there

were some baby stalactites, and Mr. Clemens stopped there

to discourse on the wonders of geology. He told me he had

lately been investigating the subject of the formation of

the earth, and he had found it so wonderful that he wanted

to know more about it. He had found some old treatises on

geology which amused him greatly, but he wanted to get some

more modern and scientific information.

And

so we wandered on, beguiled by the stream, which kept on murmuring

seductively of charms farther on.

We

talked of the Angel-fish and their many attractions. Mr. Clemens

told me of Margaret's last visit to Stormfield and of what

good times they had had together. "She is a dear womanly child,"

said Mr. Clemens, "and we had one conversation together which

convinced me more than ever of her sweet consideration for

others. She was telling me how she intended to bring up her

children, and what were her plans for their education. There

were to be two, a boy and a girl. The girl was to be named

after her mother. I asked her what the boy's name would be,

and she replied, with a reproachful look in her brown eyes:

'Why, Mr. Clemens, I can't name him until I know what his

father's name is.' Now, wasn't that truly thoughtful?"

We

finally had to leave the stream, for it was the lunch hour,

so we made an abrupt turn and approached Stormfield by the

opposite side from which we had left it. As we climbed the

hill, Mr. Clemens paused a moment to say: "I never want to

leave this place. It satisfies me perfectly."

AT

luncheon Mr. Clemens spoke of his lasting gratitude to Captain

Stormfield. For it was to the success of his Heavenly Experiences

that the building of the loggia was due. And that was the

reason the peaceful house was thus christened.

Our

meal was somewhat hurried by the announcement, made by the

deeply-interested butler, that the people were beginning to

come. We were to have that afternoon the first entertainment

of a series for the benefit of the Library Fund of the village.

Mr. Clemens had offered to tell stories, and the entrance

fee was to be twenty-five cents. Chairs had been hired from

the local under taker, and had been placed in close rows in

the big living-room, in the loggia, and out in the hall.

The

first who arrived had walked five miles. More came. They came

in buggies and in other handy vehicles. They entered the house

solemnly and took their places silently, re fusing to make

themselves comfortable, and held on grimly to fur overcoats

and fleece lined jackets. Soon the big living-room was filled

to overflowing, and then Mr. Clemens stepped up to the improvised

platform at one end of the long room and bade them welcome.

As usual, he made a most picturesque appearance. On the wall

behind him was a very large square, of carved, rich, old Italian

oak which filled the space between the two windows and formed

an effective background for the white-haired, white-clad figure

of the speaker. Mr. Clemens told story after story in his

happiest vein -- how he became an agriculturist, how he was

lost in the dead of night in the black vastness of a German

banqueting hall. He was brilliant, wonderful. He seemed determined

to bring a ripple into the faces of that silent audience.

Once in a while stern features would relax for a moment, but

the effort seemed to hurt, and the muscles would become fixed

again.

In

the back of the room there sat some of the younger generation,

who suffered from occasional apoplectic outbursts. And yet

we knew that everyone there was enjoying it deeply, hugely,

only, as Mr. Clemens said afterwards, "they weren't used to

laughing on the outside." And they were proud, too, proud

almost to sinning, of their illustrious fellow-townsman, and

they would have shouted with laughter, if they only could.

When

Mr. Clemens had finished, after an entertainment of an hour

and a half, there was no lack of applause. This they could

give. The audience dispersed slowly, many of the number stopping

to look, with open mouthed but inarticulate admiration, at

the beauties and luxuries of this home, so different from

theirs.

That

evening Mr. Clemens rested himself by playing billiards. Before

beginning, he showed me his collection of fish. Charmingly

colored pictures of Angel-fish and other varieties were framed

and hung low around the billiard-room. He told me that each

real Angel-fish who came to visit him could choose one of

those and call it her coat-of-arms. There were other very

remarkable sketches and caricatures hung on the walls, but

Mr. Clemens seemed most interested in the piscatorial collection.

It

was sometimes a wonderful and fearsome thing to watch Mr.

Clemens play billiards. He loved the game, and he loved to

win, but he occasionally made a very bad stroke, and then

the varied, picturesque, and unorthodox vocabulary, acquired

in his more youthful years, was the only thing that gave him

comfort. Gently, slowly, with no profane inflexions of voice,

but irresistibly as though they had the head-waters of the

Mississippi for their source, came this stream of unholy adjectives

and choice expletives. I don't mean to imply that he indulged

himself thus before promiscuous audiences. It was only when

some member of the inner circle of his friends was present

that he showed him this mark of confidence, for he meant it

in the nature of a compliment. His mind was as far from giving

offense as the mind of a child, and we felt none. We only

felt a kind of awe. At no other time did I ever hear Mr. Clemens

use any word which could be called profanity. But if we would

penetrate into the billiard-room and watch him play, we must

accept certain inevitable privileges of royalty.

The

next morning as I was going down stairs, Mr. Clemens called

to me from his room, in a tone that made me hurry. He was

standing by one of the many windows, and he said: "Come quickly

and look at the deep blue haze on those barberry bushes! They

have never looked quite like this before." Then he went on

to say: "When they built this house they had the inspiration

to put in these small panes. See how each one frames a wonderful

picture, and I can have a different one every time I change

my position. No man-made pictures shall ever hang on my walls

so long as I have these."

And

Mr. Clemens had no picture on his wall, except a portrait

of his daughter Jean.

That

afternoon we took a long drive over the hills. Mr. Clemens

kept no coachman and no carriage at that time, but when he

wished a "rig" he sent word to the friendly farmer near by,

who would soon appear with a surrey and a team of horses.

I

remember that much of the talk that afternoon turned on the

strange manifestations of genius and the tragic lives of many

of those who were thus fatally endowed.

When

evening came that day we asked Mr. Clemens to read Kipling

to us again, and thus revive some of the memories of the Happy

Island. And so we sat around the big blazing fire, and again

the King's voice swept us out to visions of mighty action.

More favorites were added. The Three Decker was read with

unction, and The Long Trail was read twice over before the

audience was satisfied. We wished that Mr. Rogers were there,

and, happily, we did not feel the chill prophecy that some

of us were never to see him again. An hour before luncheon,

on Sunday, we gathered together in the living-room. Some one

proposed that Mr. Clemens read aloud to us from his book,

What Is Man? Into this work Mr. Clemens had put some of his

deepest convictions as to the meaning of life and the principles

that guide the human soul. What ever may be their philosophical

value to others, he, at least, believed in them utterly, and

when he read aloud to us the clear, trenchant dialogue, we,

too, were convinced, for a time, of their truth. He grew so

earnest that he would often repeat a phrase, twice, in a deep,

solemn voice, and he so utterly forgot his pipe that it went

out completely.

Our

afternoon's peace was somewhat invaded by calls from the outside

world and demands that Mr. Clemens should allow himself to

be photographed. I often wondered how many thousand times

the camera must have turned its eye upon him.

That

last evening we played Hearts, for it still continued to be

Mr. Clemens' favorite game. Again we missed Mr. Rogers sorely,

and wished for his bantering. For no one else of us dared

to chaff Mr. Clemens in quite the way that he had done. Besides,

we knew that it wouldn't have been in the least humorous.

We lengthened the hours as long as we could, for it was to

be the last evening together, as the early morning train was

to take me away. Since we knew how averse Mr. Clemens was

to saying good-by to anyone, we parted that evening with a

simple good-night. I did not expect to see him again, but

the next morning as I went down to my hurried breakfast I

heard his voice calling me. I went to his room. He was lying

in his big carved bed, propped up by pillows. On the little

table beside him were crowded together pipes, cigars, matches,

a bottle or two, and a number of books. He handed one of the

books to me, and said, " You must have one of my souvenirs."

It was a copy of Eve's Diary, with a kindly dedication in

it on the fly-leaf. Then he said good-bye. The November sunshine

had gone. The chill of winter had come into the air, and as

I drove over the hills to the station I felt that I was going

away from something very wonderful and very precious. For

the love and friendship of those who have their faces turned

towards the sunset is sometimes as rare and sweet and unworldly

as that of little children. Perhaps they both are nearer the

infinite, and so can understand.

AFTER

the happy visit at Stormfield we never saw Mr. Clemens again,

but from time to time precious letters came from him, so characteristic

that they vividly evoked his presence. He always wrote them

in his own hand.

The

first one preserved is one that he wrote in answer to an incident

of which I had written him an account. I had been lecturing

to a class of students on Victor Hugo, and I had dwelt upon

the enthusiastic appreciation of Frenchmen for their great

men of letters. I had added, as I remember, that we had not

yet attained that advanced stage of civilization where we

could make heroes of our literary men, and, warming up to

my subject, I said that were I to ask the class sitting then

before me who was the most beloved American writer, I much

doubted if they could, spontaneously, name anyone. Seeing

nods of dissent, I challenged them, and a dozen or more responded,

"Mark Twain!" while the rest nodded approval.

His

answer is as follows --

STORMFIELD,

REDDING, CONNECTICUT,

April

22/09.

Dear

Betsy: It is not conveyable in words. I mean my vanity-rotten

joy in the dear and pleasant things you say of me, and in

my enviable standing in your class, as revealed by the class's

answer to your challenge. So I shall not try to do the conveying,

but only say I am grateful -- a truth which you would easily

divine, even if I said nothing at all.

You

must come here again-please don't forget it. We'll have another

good time.

Affectionately,

S. L. CLEMENS.

Citation:

Howells, William Dean. My Mark Twain: Reminiscences and Criticisms

(New York: Harper & Brothers, 1910; enl. BoondocksNet Edition,

2001).

To

the period of Clemens's residence in Fifth Avenue belongs

his efflorescence in white serge. He was always rather aggressively

indifferent about dress, and at a very early date in our acquaintance

Aldrich and I attempted his reform by clubbing to buy him

a cravat. But he would not put away his stiff little black

bow, and until he imagined the suit of white serge, he wore

always a suit of black serge, truly deplorable in the cut

of the sagging frock. After his measure had once been taken

he refused to make his clothes the occasion of personal interviews

with his tailor; he sent the stuff by the kind elderly woman

who had been in the service of the family from the earliest

days of his marriage, and accepted the result without criticism.

But

the white serge was an inspiration which few men would have

had the courage to act upon. The first time I saw him wear

it was at the authors' hearing before the Congressional Committee

on Copyright in Washington. Nothing could have been more dramatic

than the gesture with which he flung off his long loose overcoat,

and stood forth in white from his feet to the crown of his

silvery head. It was a magnificent coup, and he dearly loved

a coup; but the magnificent speech which he made, tearing

to shreds the venerable farrago of nonsense about non-property

in ideas which had formed the basis of all copyright legislation,

made you forget even his spectacularity.

It

is well known how proud he was of his Oxford gown, not merely

because it symbolized the honor in which he was held by the

highest literary body in the world, but because it was so

rich and so beautiful. The red and the lavender of the cloth

flattered his eyes as the silken black of the same degree

of Doctor of Letters, given him years before at Yale, could

not do. His frank, defiant happiness in it, mixed with a due

sense of burlesque, was something that those lacking his poet-soul

could never imagine; they accounted it vain, weak; but that

would not have mattered to him if he had known it. In his

London sojourn he had formed the top-hat habit, and for a

while he lounged splendidly up and down Fifth Avenue in that

society emblem; but he seemed to tire of it, and to return

kindly to the soft hat of his Southwestern tradition.

He

disliked clubs; I don't know whether he belonged to any in

New York, but I never met him in one. As I have told, he himself

had formed the Human Race Club, but as he never could get

it together it hardly counted. There was to have been a meeting

of it the time of my only visit to Stormfield in April of

last year; but of three who were to have come I alone came.

We got on very well without the absentees, after finding them

in the wrong, as usual, and the visit was like those I used

to have with him so many years before in Hartford, but there

was not the old ferment of subjects.

Many

things had been discussed and put away for good, but we had

our old fondness for nature and for each other, who were so

differently parts of it. He showed his absolute content with

his house, and that was the greater pleasure for me because

it was my son who designed it. The architect had been so fortunate

as to be able to plan it where a natural avenue of savins,

the close-knit, slender, cypress-like cedars of New England,

led away from the rear of the villa to the little level of

a pergola, meant some day to be wreathed and roofed with vines.

But in the early spring days all the landscape was in the

beautiful nakedness of the northern winter. It opened in the

surpassing loveliness of wooded and meadowed uplands, under

skies that were the first days blue, and the last gray over

a rainy and then a snowy floor.

We

walked up and down, up and down, between the villa terrace

and the pergola, and talked with the melancholy amusement,

the sad tolerance of age for the sort of men and things that

used to excite us or enrage us; now we were far past turbulence

or anger. Once we took a walk together across the yellow pastures

to a chasmal creek on his grounds, where the ice still knit

the clayey banks together like crystal mosses; and the stream

far down clashed through and over the stones and the shards

of ice. Clemens pointed out the scenery he had bought to give

himself elbow-room, and showed me the lot he was going to

have me build on.

The

next day we came again with the geologist he had asked up

to Stormfield to analyze its rocks. Truly he loved the place,

though he had been so weary of change and so indifferent to

it that he never saw it till he came to live in it. He left

it all to the architect whom he had known from a child in

the intimacy which bound our families together, though we

bodily lived far enough apart. I loved his little ones and

he was sweet to mine and was their delighted-in and wondered-at

friend. Once and once again, and yet again and again, the

black shadow that shall never be lifted where it falls, fell

in his house and in mine, during the forty years and more

that we were friends, and endeared us the more to each other.

My

visit at Stormfield came to an end with tender relucting on

his part and on mine. Every morning before I dressed I heard

him sounding my name through the house for the fun of it and

I know for the fondness; and if I looked out of my door, there

he was in his long nightgown swaying up and down the corridor,

and wagging his great white head like a boy that leaves his

bed and comes out in the hope of frolic with some one.

The

last morning a soft sugar-snow had fallen and was falling,

and I drove through it down to the station in the carriage

which had been given him by his wife's father when they were

first married, and been kept all those intervening years in

honorable retirement for his final use. Its springs had not

grown yielding with time; it had rather the stiffness and

severity of age; but for him it must have swung low like the

sweet chariot of the negro "spiritual" which I heard him sing

with such fervor, when those wonderful hymns of the slaves

began to make their way northward.

Go

Down, Daniel, was one in which I can hear his quavering tenor

now. He was a lover of the things he liked, and full of a

passion for them which satisfied itself in reading them matchlessly

aloud. No one could read Uncle Remus like him; his voice echoed

the voices of the negro nurses who told his childhood the

wonderful tales. I remember especially his rapture with Mr.

Cable's Old Creole Days, and the thrilling force with which

he gave the forbidding of the leper's brother when the city's

survey ran the course of an avenue through the cottage where

the leper lived in hiding: "Strit must not pass!" Out of a

nature rich and fertile beyond any I have known, the material

given him by the Mystery that makes a man and then leaves

him to make himself over, he wrought a character of high nobility

upon a foundation of clear and solid truth. At the last day

he will not have to confess anything, for all his life was

the free knowledge of any one who would ask him of it. The

Searcher of hearts will not bring him to shame at that day,

for he did not try to hide any of the things for which he

was often so bitterly sorry. He knew where the Responsibility

lay, and he took a man's share of it bravely; but not the

less fearlessly he left the rest of the answer to the God

who had imagined men. It is in vain that I try to give a notion

of the intensity with which he pierced to the heart of life,

and the breadth of vision with which he compassed the whole

world, and tried for the reason of things, and then left trying.

We had other meetings, insignificantly sad and brief; but

the last time I saw him alive was made memorable to me by

the kind, clear judicial sense with which he explained and

justified the labor-unions as the sole present help of the

weak against the strong.

Next

I saw him dead, lying in his coffin amid those flowers with

which we garland our despair in that pitiless hour. After

the voice of his old friend Twichell had been lifted in the

prayer which it wailed through in broken-hearted supplication,

I looked a moment at the face I knew so well; and it was patient

with the patience I had so often seen in it: something of

puzzle, a great silent dignity, an assent to what must be

from the depths of a nature whose tragical seriousness broke

in the laughter which the unwise took for the whole of him.

Emerson, Longfellow, Lowell, Holmes -- I knew them all and

all the rest of our sages, poets, seers, critics, humorists;

they were like one another and like other literary men; but

Clemens was sole, incomparable, the Lincoln of our literature.

2004 Aerial of Jean's

Farm and Stormfield

(it's on the left

side of road, the right is Lee Lane and Glen Hill Road)

The

Mark Twain Trail

The

Mark Twain Trail is a map

of people and places connected to Mark Twain's years in Redding,

Connecticut that Susan Durkee prepared in 2006. Susan Durkee

is a very talented artist and a huge fan of Twain that just

happens to live in a house that sits on the foundation of

the Lobster Pot (which was lost to fire in 1953). I have added

an online version of Susan's map via Google

Maps. The map contains the following:

1.

Stormfield. Mark Twain's last home. Twain, encouraged

by his biographer, Albert Bigelow Paine, bought the 248 acre

property in 1906, sight unseen. A year later, he hired John

Mead Howells to design an 18 room, two story Italianate Villa.

Mark Twain's daughter, Clara Clemens, selected the location

for the house, and Isabel Lyon, his secretary, helped supervise

its construction.

2.

The Lobster Pot. A circa 1720 saltbox located on Mark

Twain Lane, a part of Twain's 248 acre Stormfield property.

He called the house the "Lobster Pot" as it reminded him of

lobster pots he had seen in Maine...the name may also tie-in

to Twain's Aquarium as Isabel Lyon lived in this house and

it's possible Twain or one of his Angelfish may have playfully

referred to Isabel's house as the Lobster Pot. Original house

was lost to fire in 1953, but the gardens and patios remain.

3.

Markland. Twain gave his biographer, Albert Bigelow Paine

a seven acre parcel of land upon which to build a studio,

yet insisted that Paine adapt the studio to accommodate a

billiards table; "then when I want exercise. I can walk down

and play billiards with you, and when you want exercise you

can walk up and play billiards with me."

4.

Albert Bigelow Paine's house. It was through Paine that

Twain discovered Redding. During the last four years of Twain's

life, Paine became a virtual member of the family. Paine's

house was an an antique saltbox, which partially burned down

in the 1960's, one original wing remains on Diamond Hill Rd.

5.

Umpawaug Chapel. On October, 28, 1908, Twain dedicated

a nearby chapel as the temporary location for the Mark Twain

Library. He donated thousands of books from his personal collection.

The library was actively used, and a librarian was on hand

Wednesday and Saturday afternoons.

6.

W.E. Grumman's House. Grumman was Twain's stenographer,

he was also the first librarian of the Mark Twain Library.

7.

A.H. Lounsbury House. Lounsbury was Twain's caretaker

and livery man at Stormfield. Lounsbury along with Sheriff

Banks, helped capture the two burglars who robbed Stormfield

in 1908. Twain always gave credit for the success of their

capture to Lounsbury.

8.

The Mark Twain Library. The library officially opened

at its present location on February 18, 1911.

9.

Stormfield Barns and Two Family House. The only original

buildings remaining at Stormfield- a two-family house, large

stable, chicken coop and outbuildings.

10.

Jean's Farm. Twain purchased this farm, which abutted

his own property, for his daughter Jean Clemens. Jean joyfully

filled the farm with a collection of poultry and domestic

animals during her time in Redding. Tragically, she died on

Christmas eve, 1909 and Twain promptly had the property sold

to build a wing in her honor at the new Library.

11.

Theodore Adams' House. Mr. Adams donated the land where

the Mark Twain Library sits today at the corner of Diamond

Hill Rd. and Route 53. Of course, he needed a little coaxing

from the founder himself.

12.

Dan Beard's House. Dan Beard was Twain's illustrator and

devoted friend. Among the many books and stories he illustrated

for Twain included: A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's

Court, Following the Equator, American Claimant, Tom Sawyer

Abroad. He designed the wreath for Twain's funeral and published

a eulogy to him in the American Review of Reviews.

13.

West Redding Train Station. On June 18, 1908, just before

6pm, the Berkshire Express out of NYC made a special stop

for Mark Twain's first visit to Redding, Connecticut. The

railroad continued to make this special stop from that day

on in order to accommodate Twain and his many visitors to

Stormfield.

View

Tour of Mark Twain's Redding via Google

Maps.

The

Sunderlands of "Stormfield"

Mr.

Philip Nichols Sunderland, looking back on a long and active

life, takes particular joy in remembering two things: that

he is one of the relatively few people still alive who voted

for Grover Cleveland, and saw Mark Twain arrive in Redding.

It takes a rather particular talent to have been able to do

these two things, but Mr. Sunderland has it- he turned 87

on June 1, 1958, and to all appearances will be able to recall

these memorable happenings for a good many years to come.

The

vote for Grover Cleveland was cast in 1892, when he had just

turned 21. Mark Twain's arrival came 16 years later, and Mr.

Sunderland had good reason to be present: he and his father

William Webb Sunderland, built the house Mark Twain moved

into, the "Stormfield".

The

Sunderlands (three generations) never in their many years

of building in and around the Danbury area had a job quite

like this one. "The first time I ever saw Mr. Clemens, was

in the house on Eighth in New York, when I went there with

John Meade Howells, the architect, to get the contract signed.

The house was designed by that time, the plans were all ready,

but the site had not been selected. Mr. Howells came out a

little later and approved it. Mr. Clemens I did not see again

until the day he moved in. He never saw the site, or the house

while it was being built; all he did was sign the contract.

His first sight of the entire project was the finished place,

painted, furnished and ready for occupancy right down to the

cat purring on the hearth."

As

Mr. Sunderland recalls it today, "it was really Mr. Paine,

his friend and biographer, who planned the whole thing. He

and Harry Lounsbury found the site, and I could feel the influence

of Mr. Paine on the whole performance. Miss Lyon, Mr. Clemens

secretary at that time, decided all the interior decoration.

She picked out everything; Mr. Clemens had complete confidence

in her, and left everything to her discretion. "I remember

once," Mr. Sunderland continued with a smile, "when we had

the whole interior finished, painted white, and Miss Lyon

decided she didn't like it. The house was supposed to look

like an Italian Villa; she felt we had made it look like a

New England Colonial place. She said what it needed was a

dark stain- so we did the whole place over again in the dark

stain..."

It

was a big house, Mr. Sunderland recalls- big, comfortable

and friendly. Of particular importance was the billiard room.

"Mr. Clemens loved billiards; the game was really his hobby,

and he played there a great deal with Mr. Paine and the little

girls." And there were parties there which he recalls, having

been a guest in the house he helped to build. "The biggest

party I ever saw there, was when Ossip Gabrilowitsch gave

a concert there one evening (09/21/09), who married Clara

Clemens. There were lots of people from New York, and a very

well known singer (David Bispham) of the time whose name now

escapes me.; and I recall particularly the Gabrilowitsch,

having recently been operated on for a mastoid infection,

still had a patch of sticking plaster over one ear."

And

Mr. Clemens? "Ah, he was a striking figure of a man, impressive.

He was also a very sentimental person, particularly with children."

"The

day he arrived, I went down to be present, as a representative

of my father, at his entry into the house. It was all rather

informal, I recall; there were quite a lot of people who came

out with him on the train from New York and we all drove up

from the Branchville station (he says Branchville but that's

incorrect, unless a photo surfaces to prove otherwise, Twain

arrived in West Redding) in buggies. And it was all there,

just as he had wanted it, even to the cat and I believe that

he was very pleased.

"I've

never been back there since Mr. Clemens died. We've done a

great many things since then, of course, and incidentally,

my association with John Meade Howells grew into a lifelong

friendship and led to his designing several buildings in this

area, including the First Congregational Church in Danbury-

but I will always remember Mr. Clemens' house. It was a unique

experience."

Percy

Knaut interviewed Philip N. Sunderland in 1958 for the Redding

Times.

Other

History of Redding pages related to Mark Twain:

The Stormfield

Project has begun, you can track it via my Mark

Twain Stormfield Project blog. Below are some

posts.

Twain's

Time in Redding:

Stormfield:

Mark

Twain Library:

Mark

Twain Centennial Art Collection:

Mark

Twain's "Lobster Pot" Studio & Gallery is honored

to present a special limited edition "Centennial

Collection" of prints commorating Mark Twain's last

years in Redding, CT and his death at Stormfield, his Redding

home, April 21, 1910. Portrait

Artist, Susan Boone Durkee, who lives on the original

property which Mark Twain called "The Lobster Pot"

is pleased to present this exclusive limited edition of prints

using the highest quality of archival inks and paper available.

Please view the Mark

Twain Gallery of her artwork honoring America's most

famous writer and humorist.

Photos

of Stormfield

New

York Times Articles about Mark

Twain in Redding, CT

The

Stormfield Project has begun, you can track

it via my Mark

Twain Stormfield Project blog.

I update this blog quite often*

The

Connecticut Mark Twain Connections Google Map

For

the latest updates on our Twain 2010 projects, follow

us on Twitter.

The Burglary at Stormfield

www.twainquotes.com

Great Resource

www.twainweb.net

The Mark Twain Forum (amazing insights).

Here's

a scrapbook with pictures of Stormfield from PBS. Click Here.

Resource

with links to Twain related sites

The

Stormfield Project has begun, you can track it via my Mark

Twain Stormfield Project blog.

| |

|

|

| |

Inventing

Mark Twain:

The Lives of Samuel Langhorne Clemens

by Andrew Hoffman

*Includes Redding info.

|

|

Back

to TOP | Back to Redding

Section | Back to Georgetown

Section

|

|